The big American Heart Association (AHA) conference is in full swing, and this year we get to look forward to a number of important clinical trials. Perhaps the most anticipated of which is the SELECT trial, published in NEJM this morning (November 11th). I have already seen a lot of hype around this trial, and words like “game changer” are circulating. I’m less enthused after reading it, probably because I’m not there in person, soaking in the energy of the conference.

Link here, “Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes”

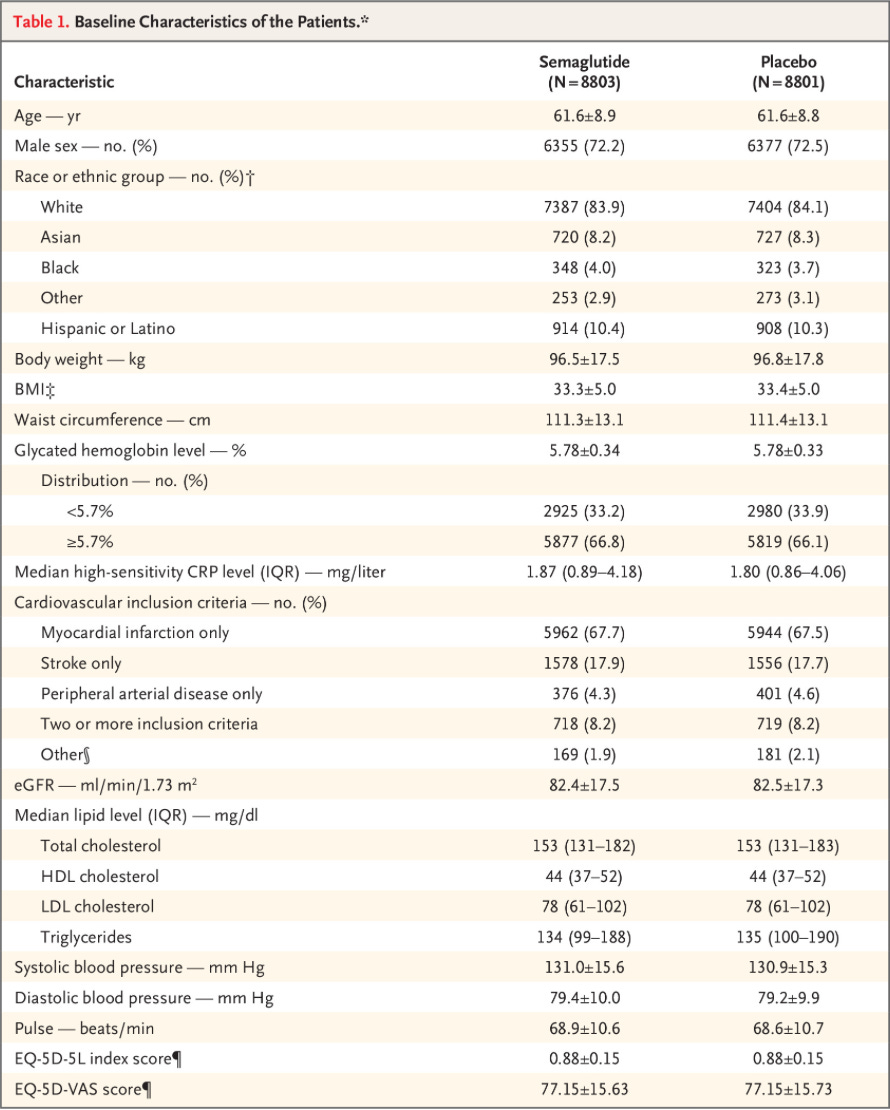

Study Population: This was a large secondary prevention study. Patients were required to have established cardiovascular disease. Average age was just over 60 years, average BMI 33, average baseline A1c 5.78. Two thirds of the patients met criteria for pre-diabetes (HbA1c 5.7-6.4). 76% of patients had a history of previous MI (Table S1). In other words, and as the table below shows, this was a high risk cohort.

Intervention: 17,604 patients randomized 1:1 to once-weekly injection of 2.4mg semaglutide vs. placebo. Mean duration of follow-up was 39.8 months.

Results: The primary cardiovascular end-point event was a composite of the following: death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke. Here are the results:

Initial thoughts: Primary outcome was positive, the first confirmatory secondary outcome was negative, so the other two unable to be assessed, due to the statistical plan. Despite the negative results for confirmatory end points, the data are still encouraging. It’s worth noting that the confidence intervals for the supportive secondary end points are not adjusted for multiplicity.

I like to look at overall survival, and we see a 0.9% absolute risk reduction for death from any cause. You can also see that semaglutide seemed to attenuate the incidence of diabetes in this largely pre-diabetic patient population. Patients in the treatment arm lost about 10% of body weight on average. Below are these and other additional end points:

Tolerability/Safety: Patients were twice as likely to discontinue treatment due to adverse events in the treatment arm, ~16% and 8% for semaglutide vs placebo, respectively.

My thoughts: The average duration of treatment was 33 months. If we take the results at face value, we can start with the primary composite outcome and then look at all-cause mortality.

Primary composite (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke): If you give semaglutide 2.4mg weekly to 100 high risk patients with established cardiovascular disease for just under three years, you can prevent 1.5 events.

All-cause mortality: If you give semaglutide 2.4mg weekly to 100 high risk patients with established cardiovascular disease for just under three years, you can save 0.9 lives.

This framing demonstrates why I am not jumping for joy at these results. Even in this high risk, secondary prevention study, it took randomization of over 17,000 patients and treatment for almost three years on average to show this benefit. I’m not saying it’s nothing, but it seems marginal.

Now I think it is worth highlighting the odd divergence following 36 months on treatment. Go back and look at the figures that show the major outcomes. If you stopped measuring at 36 months, or three years of treatment, the trial would be a wash. Less than half of the patients are included in the data once you get to 42 months. I’m not sure what, if anything, to make of this. But assuming it simply takes that long for a meaningful difference to emerge, that is sobering for the possible cost-benefit.

Of course it has to be mentioned that unlike bariatric surgery, which is a one time intervention, patients must continue to take semaglutide indefinitely in order to avoid regaining weight. Lean body mass was not addressed in this study, which is a huge miss. This length of treatment affords an excellent chance to determine possible effects on strength and muscle mass, a concern with GLP1 agonists.

It’s worth noting that while this study didn’t seem to depend on subjective measures, maintenance of blinding likely wasn’t achievable. The combination of gastrointestinal side effects and reliable weight loss make it difficult to imagine that patients or their clinicians remained blinded for long. This claim has some support if you look at supplemental figure S1. 2.7% of patients on placebo cited “lack of effect” as the reason they did not complete treatment. Only 0.7% of the treatment group cited this reason.

Additionally, “Treatment with an open-label GLP-1 receptor agonist was initiated during the trial (a violation of the trial protocol) in 36 patients (semaglutide in 28 patients) in the semaglutide group and in 121 patients (semaglutide in 92 patients) in the placebo group.” This asymmetry in perceived effect suggests blinding was not maintained. I wasn’t able to find the composition of the placebo.

All in all I’m not particularly enthused by these data. Let me know if anyone has thoughts, disagreements, etc. Happy Veterans Day.

With NNT of 100 for 0.9 lives saved from all cause mortality, reported in this study, I look pretty hard at side effects of treatment with semaglutide. They can be pretty severe. My 27 year old physical trainer was using that stuff, became chronically constipated and ended up with his appendix removed. I go to askapatient.com and search for the side effects of these meds and it's sobering.

I want to say, that I have enjoyed your reviews. Especially your deep dive and summaries of trials surrounding Entresto, they have been helpful to review. I have been following your work along with the Sensible Medicine folks with a lot of interest. Especially the fact that you are doing any of this while a medical student, I barely could eat three meals a day and finish my regular studying.

For your review, I was a little surprised by your lack of enthusiasm. I feel like following more staunch EBM folks, I worry that can lead us down a nihilist path. I think this trial is fairly impressive, but I think you main frustration was just that the effect size was not as large as you would have hoped. It was interesting to compare your review to Dr. Mandrola’s. https://www.sensible-med.com/p/a-major-breakthrough-in-obesity-treatment?r=oe9qx&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

We have been using GLP-1 for control of T2DM, improvement in surrogate A1C, and now you tell me that it could actually improve mortality? That is just a bonus! I think this is going to have a huge impact if insurance companies are going to cover for people who are prediabetic. Some insurers are only allowing Wegovy, which this is. This 2.4 mg dosing is Wegovy.

Outside of the comment below, people also really want to be on Ozempic/Wegovy. I have patients ask me for it all the time. We understand the GI side effects, and they are obviously more pronounced on the treatment arm. This dose is also the big kid dose of Ozempic.

I share your concern about where patient’s weight is being lost, and would be interested to know about fat vs muscle loss. There is a concern about rebound weight gain if we are to remove these agents.

I was curious if you had any great explanation for that larger fluctuation late in the trial period or any other criticisms that would call anything into question. I share your concern that blinding was difficult to maintain given I suspect many patients might be able to tell given the GI side effects. But, when considering the hard outcomes that seems less of a concern as you note.

Overall, I thought this might have been one you had more enthusiasm for. It is a fairly well run trial, provided some hard outcomes, and for a relatively safe drug that people really want. It really won’t change my practice too much, but I suspect there are fewer and fewer reasons to hold back on GLP-1s for patients with CAD, T2DM, and/or Prediabetes. Thanks for your post.