Ozempic = Semaglutide = Wegovy

Ozempic is now widely known as an effective weight-loss medication. The irony is that Ozempic is approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), not weight loss. Semaglutide is the generic drug name of Ozempic; I will use these names interchangeably. Though we will not talk about it in this post, “Wegovy” also refers to semaglutide, but in that case the dose is higher and the FDA indication is obesity, rather than T2DM.

There is an article from the other day in the NYT that covers some of the history behind these medications. Do read that if interested, I will get straight to the trials for the sake of brevity. I particularly enjoy the NYT article’s coverage of the origin of these drugs being linked to the saliva of the Gila monster.

Semaglutide for Type 2 Diabetes: SUSTAIN Trials

There are many SUSTAIN trials. We will focus on the most important study, SUSTAIN 6. Let’s review some of the major FDA approvals for Ozempic:

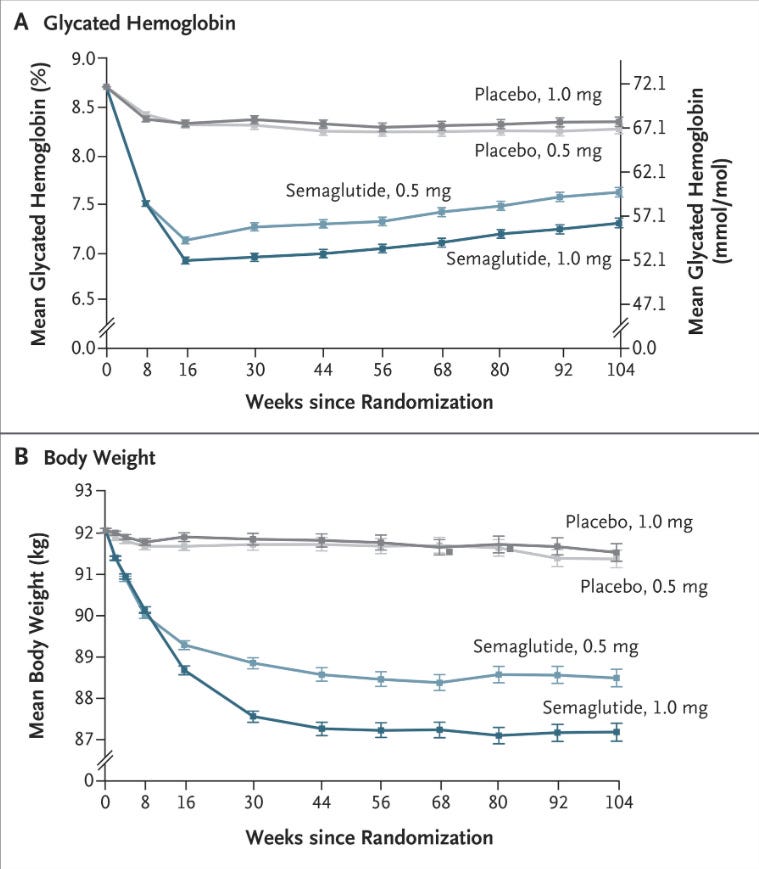

The FDA approved Semaglutide in 2017 for the treatment of adults with T2DM. The FDA cited SUSTAIN trials 1-6 in this approval. While SUSTAIN 6 is the most important overall, the other studies consistently demonstrated Semaglutide’s powerful effects on HbA1C and body weight. For anyone interested, the end of this post will include some limited data on SUSTAIN 1-3 and one-liner takeaways of SUSTAIN 4 and 5.

The FDA approved Semaglutide in 2020 for cardiovascular risk reduction in adults with T2DM and known heart disease. This decision was almost entirely based on SUSTAIN 6 specifically.

SUSTAIN 6: “Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes”

Published in 2016 in the NEJM.

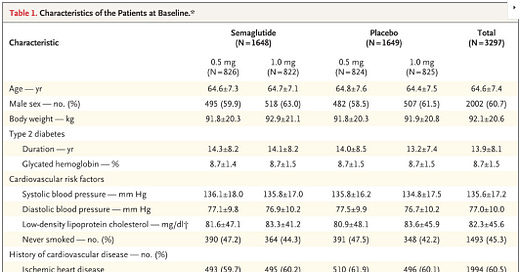

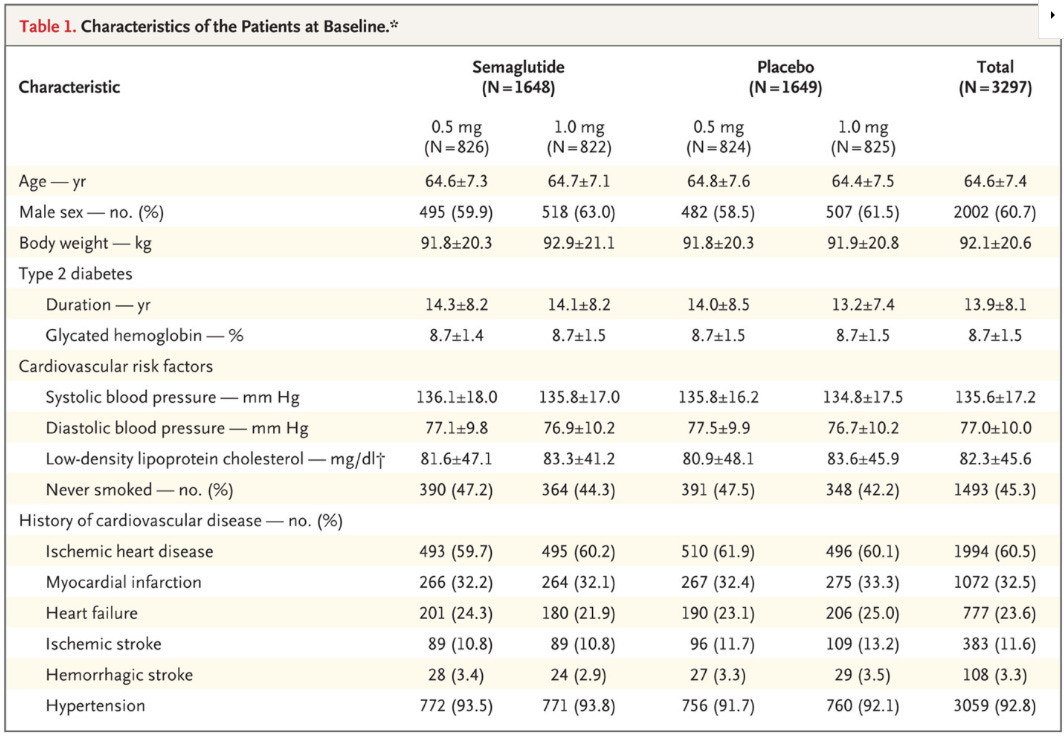

Trial Design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT at 230 sites in 20 countries.

Interventions: Patients randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive either 0.5mg or 1.0mg of once-weekly semaglutide or volume-matched placebo.

Inclusion: This was largely a secondary prevention study. All patients were either over 50 y/o with established cardiovascular disease, chronic heart failure, CKD stage 3+, or over 60 y/o with risk factor(s).

Outcome Measures:

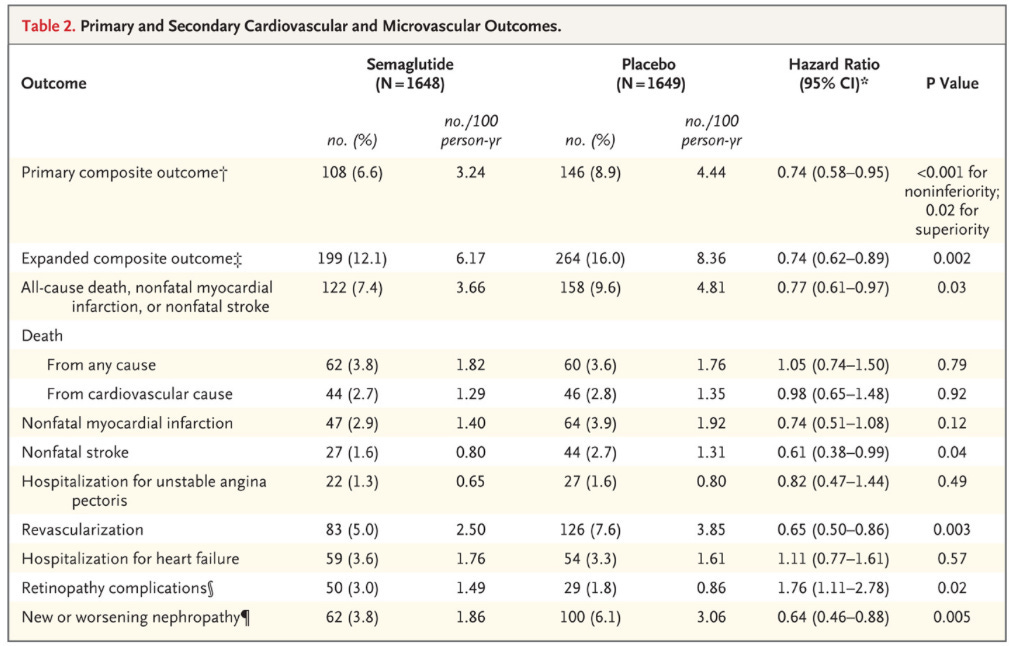

Primary composite: First occurrence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI (including silent), or nonfatal stroke.

Secondary outcomes:

Expanded composite of primary outcome + revascularization and hospitalization for unstable angina or heart failure.

Additional composite: All-cause mortality + nonfatal MI + nonfatal stroke

Stats: Of note, this was a non-inferiority trial. Superiority testing was not prespecified or adjusted for multiplicity.

Participants: 3,297 patients underwent randomization. Median observation time was 2.1 years.

Results: I’m going to drop all the figures/tables so you can think through it before getting to my interpretation.

My interpretation of results: SUSTAIN-6 is the reason why GLP-1 agonists are said to improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM. That really can only be said for a secondary prevention cohort. 83% of patients included had established cardiovascular disease. Let’s start by taking these results at face value.

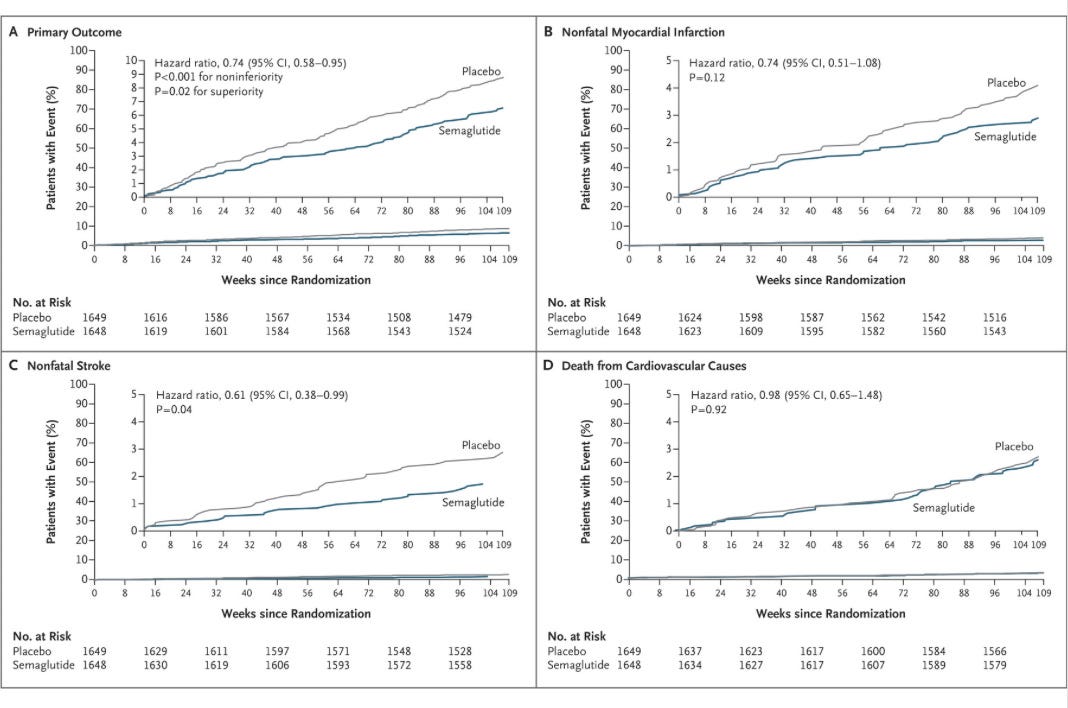

Primary End Point: First occurrence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI (including silent), or nonfatal stroke.

There was a 2.3% absolute risk reduction observed in the treatment groups.

As we have talked about in previous posts, composite endpoints can be misleading. Death and a silent MI are not equivalent outcomes, so they must be parsed.

If you haven’t yet, scroll up and peruse the outcomes in table 2. Both all-cause death and cardiovascular death were unchanged during this trial. The benefit in the primary outcome is derived from:

1.1% absolute risk reduction in nonfatal stroke, which was statistically significant.

1% absolute risk reduction in nonfatal myocardial infarction, which was not statistically significant.

Supplementary table S9 breaks down some of these outcomes further. I think it’s worth noting that the absolute risk reduction for acute myocardial infarction was a less impressive 0.5%.

My summary of these findings: If you treat one hundred ~60-70y/o patients with longstanding (>10yrs) T2DM and established cardiovascular disease with semaglutide for two years, you will prevent one nonfatal MI and one nonfatal stroke.

That is not as sexy as the framing the authors gave the same results: “Semaglutide-treated patients had a significant 26% lower risk of the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke than did those receiving placebo.”

Both are true. Theirs was written in partnership with Novo Nordisk, mine wasn't.

My take is that the RCT evidence supporting cardiovascular risk reduction from Ozempic shows marginal benefit. This of course does not mean GLP-1 agonists as a class, or even Ozempic specifically, have only marginal benefit. My claim is specific to cardiovascular outcomes.

There are other important considerations, such as tolerability and the increases in heart rate, lipase, amylase, and retinopathy complications in this trial. The drug is undeniably effective at lowering HbA1C and body weight, and we saw a decrease in systolic blood pressure.

Open question: I was unable to find specifics regarding the composition (eg, saline) of the placebo in the supplementary appendix or the protocol. Unfortunately my time spent reading trials designed and reported by pharmaceutical companies has taught me to follow up on this information. I don’t know if this played any role in the short-term side effect profile of the placebo. The dose-dependence piqued my interest, but it could just be local effects due to volume. If anyone does know the details please let me know.

What do I think Ozempic is good for?

Ozempic is a powerful medication that can be quite useful in some situations. I’m impressed with its effect on glycemic control and weight loss, with some caveats given the requirement to continue taking the medication for sustained weight loss. In my mind I think of it as a good backup medication for metformin in patients who are unable to control T2DM with lifestyle interventions. Insurance coverage and cost both factor in here, and I would want to be sure a patient was not putting themselves on a path to sarcopenia. I think of these medications as a similar lever to pull with respect to severity of disease as bariatric surgery. That may sound extreme to some, but in both cases you are resorting to an extreme intervention. In one case it’s going under the knife, the other is taking weekly injections indefinitely in a last-ditch attempt to control disease.

A sleeve gastrectomy dramatically reduces the size of the stomach, promoting satiety following much smaller meals. GLP-1 agonists slow gastric emptying, effectively putting the gastrointestinal system in slow motion. This similarly promotes satiety. I would like to see a repeat of STAMPEDE, which compared bariatric surgery with intensive medical therapy for diabetes. (I linked to the 5-year follow up paper). The large caveat with that study is that it was conducted prior to the approval of semaglutide for T2DM.

Looking Forward: The STEP trials look at the use of Semaglutide/Wegovy in obesity. Most importantly, and imminent, is the SELECT trial. This is a large trial powered for cardiovascular outcomes. Novo Nordisk announced positive results of the trial earlier this month, but it has yet to be published. Further down the road we will cover the relevant trials for Tirzepatide, and we may talk about Retatrutide’s recent phase two trial.

Note: This is the end of the main post. For any interested in some of the earlier SUSTAIN trials:

Appendix: SUSTAIN 1-5

SUSTAIN 1: April 2017, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology

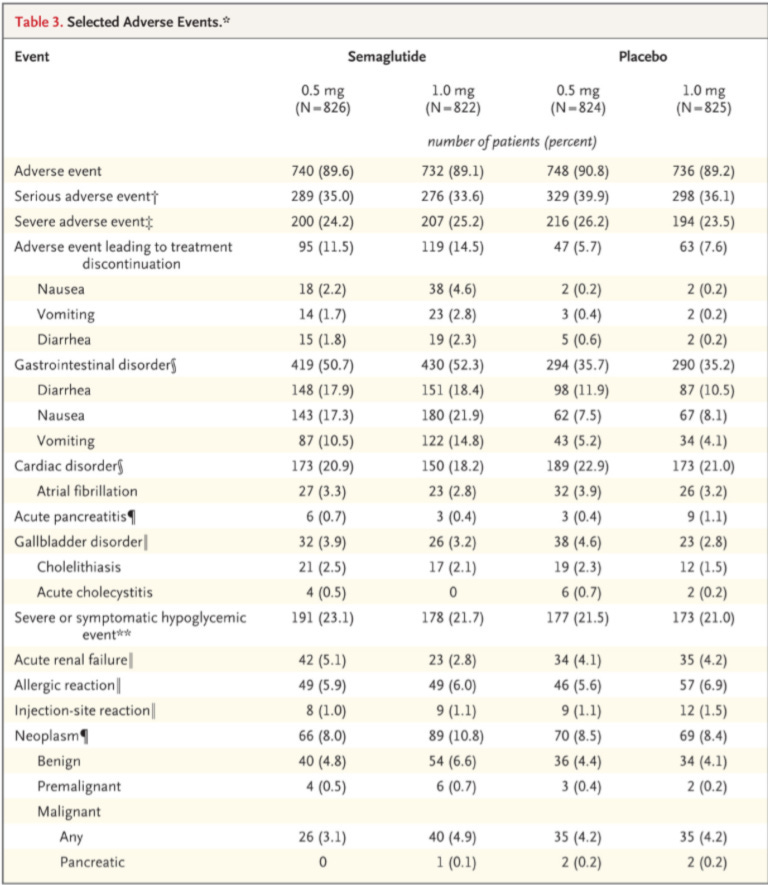

This was a small study, they randomly assigned 388 participants (2:2:1:1) to once-weekly semaglutide injection (0.5mg or 1.0mg) or volume matched placebo.

These were adult patients with T2DM, HbA1c 7-10%, treatment naive

Primary outcome was change in mean HbA1c from baseline to week 30

Secondary outcome was change in mean bodyweight over the same timeframe

Pros: Semaglutide looks promising, with significant improvements in both HbA1c and weight.

Cons: GI side effects were frequent, though mostly limited in severity. These included nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Lipase and amylase levels were significantly increased in both treatment groups. Four cases of cholelithiasis were reported, none of which were in placebo.

Note: Mean heart rate increased significantly with each treatment arm, relative to placebo.

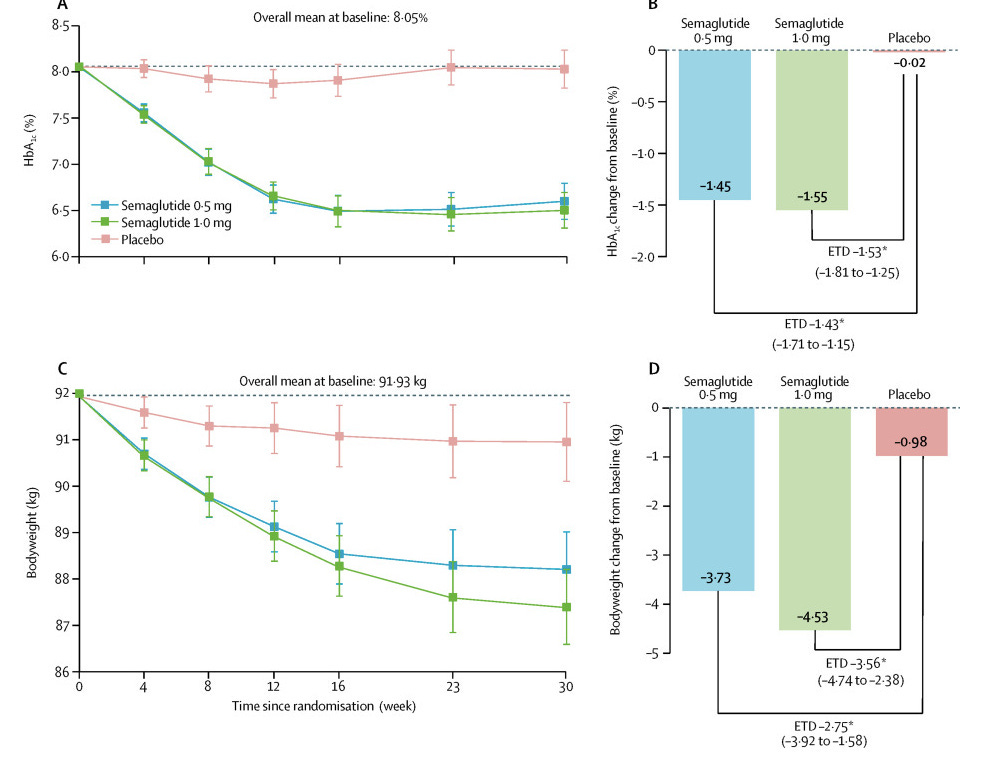

SUSTAIN 2: May 2017, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology

This was more of a medium-sized study. Thankfully the supplement has a beautiful image that sums up all of the basic study details:

Same primary and secondary outcomes as before.

Results for HbA1C:

Results for weight:

Pros: Similar picture here, better results for key outcomes of HbA1c and weight compared to sitagliptin.

Cons: Also fairly consistent. Lots of GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). For adverse events leading to premature discontinuation: 8% of the semaglutide 0.5mg, 10% of the 1mg group, and 3% of placebo. 3 events acute pancreatitis in 0.5mg group, 1 chronic pancreatitis in 1mg group, none in sitagliptin group. Amylase and lipase levels higher in both semaglutide groups, relative to sitagliptin.

Note: Pulse rate increased by 1.6 beats per min with 0.5mg, 1.8 in 1mg group.

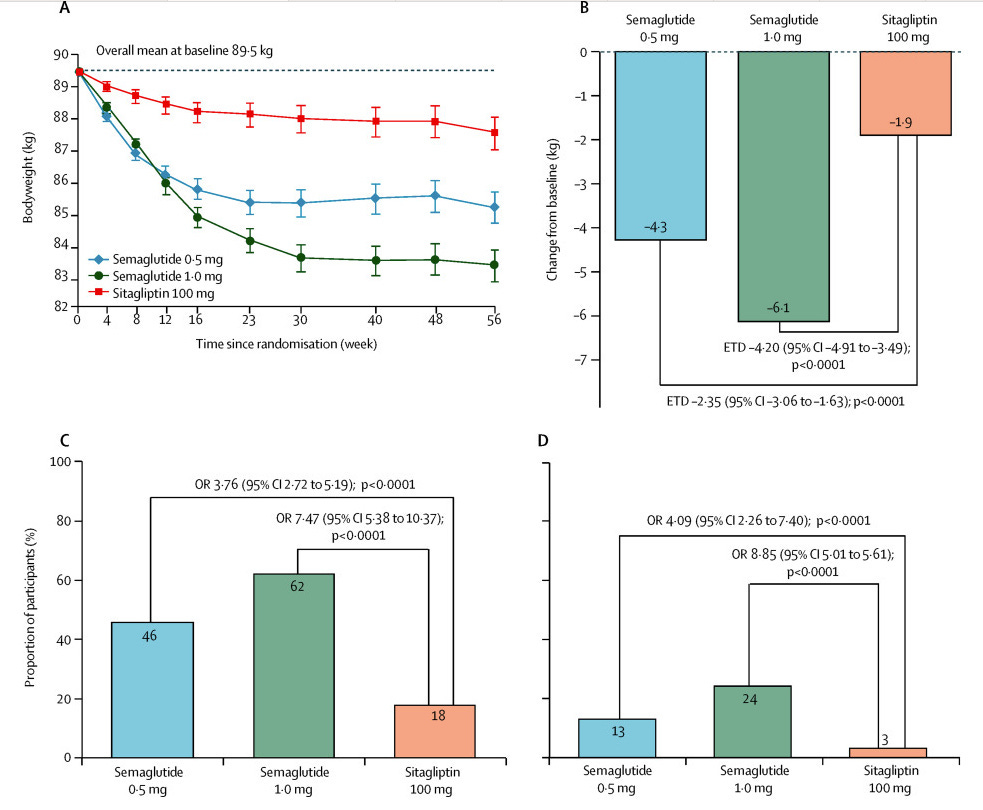

SUSTAIN 3: December 2017, Diabetes Care

Design:

Results:

Take home: 1mg Semaglutide looks better than 2mg Exenatide.

SUSTAIN 4: Semaglutide non inferior to insulin glargine. This was open-label, some question around titration of glargine.

SUSTAIN 5: Semaglutide vs. placebo as an add-on to insulin in T2DM. HbA1C reductions were significantly improved with use of semaglutide.

I really suspect the placebo had to have been active in some way based on the amount of side effects reported from it. It's a very odd thing to see but not uncommon to see placebo slanted in a way that it obscures some of the side effects that are 100% caused by the active ingredients.

The other question I have is that in the 2 year graph, the HBA1C control seems to decrease with longer use. I wonder how that graph would look if it was extended out to 5 years. Would the benefit turn out to be medium term and decrease in the long term as the effects of the medication accumulated? Is it possible there could be a negative effect in a 5 year time window that might mean doctors shouldn't be prescribing to those patients who are in their 30's and 40's? (I know people in their 40's who are on it.)

One other question - have you been following the discussion on risk of going under anesthetic while on it? There is some discussion among anesthesiologists about increased risk of anesthetic complications due to delayed gastric emptying and they don't know the right length of time it should be stopped prior to anesthesia as of yet.

Am also curious your thoughts about those who are using it as a designer drug for weight loss without having tried anything else. Seems to be a bit like a fad in that regard but not without risk?

How did they calculate the 26%?