Zuranolone paper

Today we will focus on a recent trial of nirsevimab, the monoclonal antibody given to infants for prevention of lower respiratory tract disease from RSV. Before doing that, I’d like to plug a recent opinion piece that we did for JAMA. Linked here, we discussed some concerns regarding what I think is a low quality FDA approval of zuranolone. This is a postpartum depression approval, the final paragraph of our opinion sums it up decently:

“The FDA saw fit to approve zuranolone based on modest efficacy data in trials that compared it with substandard medical care. This medication has significant limitations, including misuse potential, impaired psychomotor functioning, lack of compatibility with breastfeeding, and anticipated exorbitant cost. We suggest that the FDA require control groups that reflect standards of care to better inform and equip physicians with medications that might improve the health of patients, and we caution the current use of zuranolone.”

HARMONIE

This is an open-label trial of nirsevimab (brand name Beyfortus), the monoclonal antibody that was approved in 2023 for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease. Link is here, let’s go over the basics:

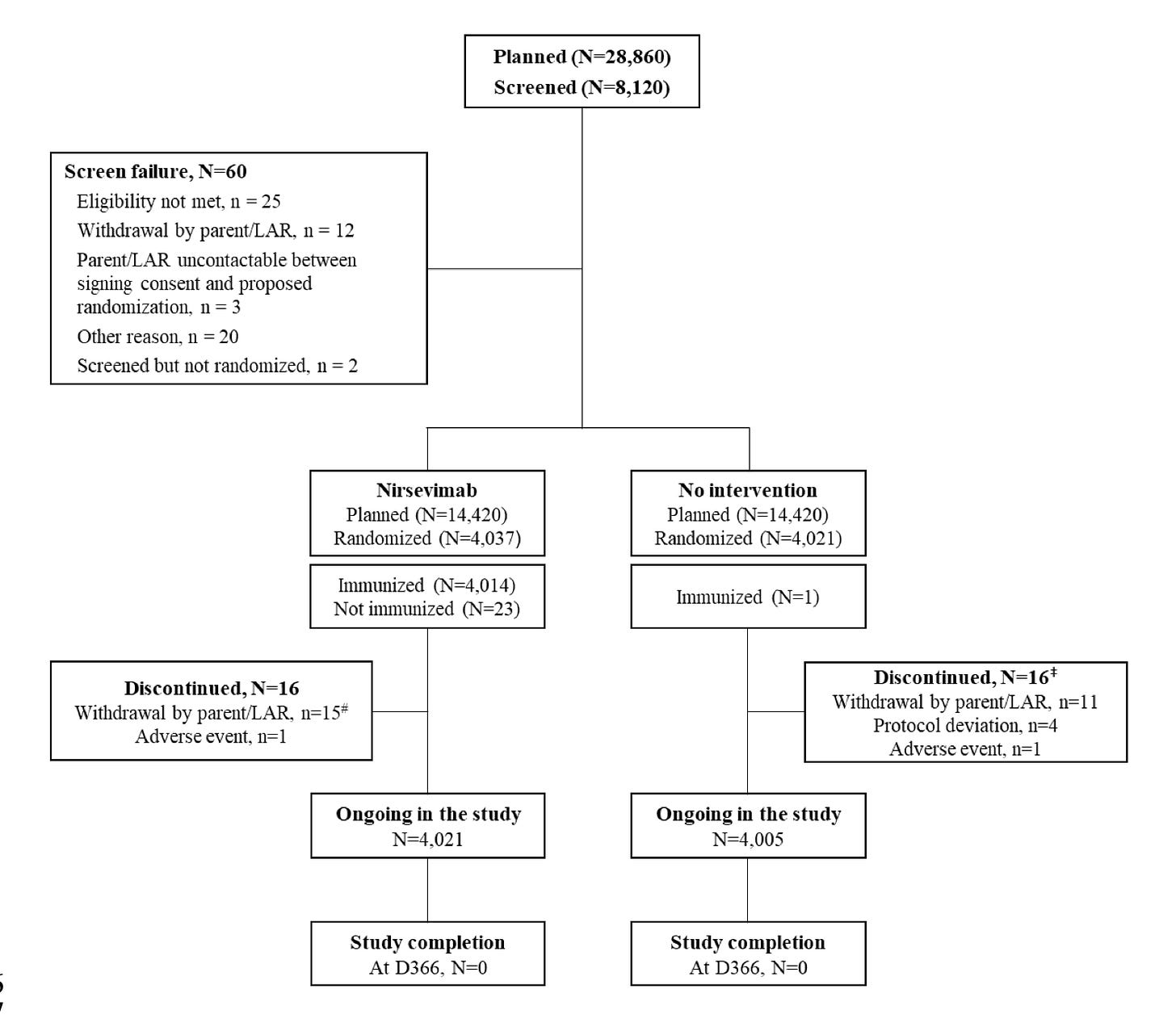

Design: This was a pragmatic, open-label trial, in which they “randomly assigned 8058 infants to receive nirsevimab (4037 infants) or standard care (4021 infants).”

The trial was done in the UK (~51%), Germany. (~27%), and France (~22%).

Participants: “Healthy infants who were 12 months of age or younger, had been born at a gestational age of 29 weeks or more, and were entering their first RSV season were eligible for inclusion.”

Some important exclusion criteria included:

Active confirmed RSV infection at the time of dosing/randomization

Active LRTI at the time of dosing/randomization

Mother of the infant participant was administered an RSV vaccine during her pregnancy with the infant participant

End Points:

Hospitalization for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection (Primary end point)

Very severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection (defined as hospitalization for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection with an oxygen saturation <90%)

Hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infection from any cause

Note: This publication is the preliminary analysis, and the trial is ongoing. They got the efficacy data they wanted, so they closed recruitment, but one year of follow-up is needed before they can report the final data. The downside of closing recruitment is that the total population is just over 8,000, whereas they originally planned for 28,860 overall. There were more events than expected, allowing efficacy to be more readily assessed, the obvious downside being less safety data in the end. The flowchart below from the supplement shows this:

Efficacy Data

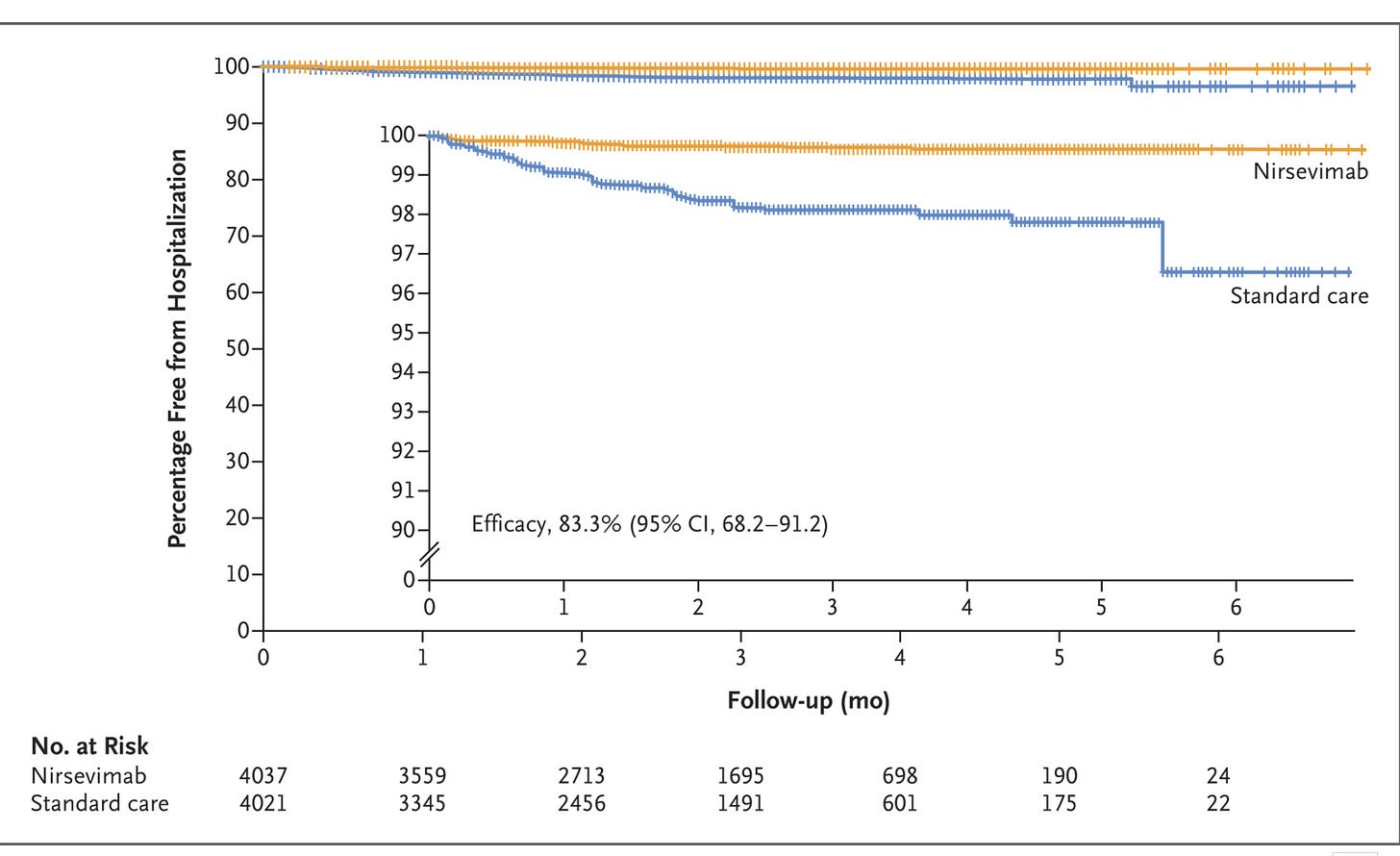

Primary end point of hospitalization for RSV-associated LRTI:

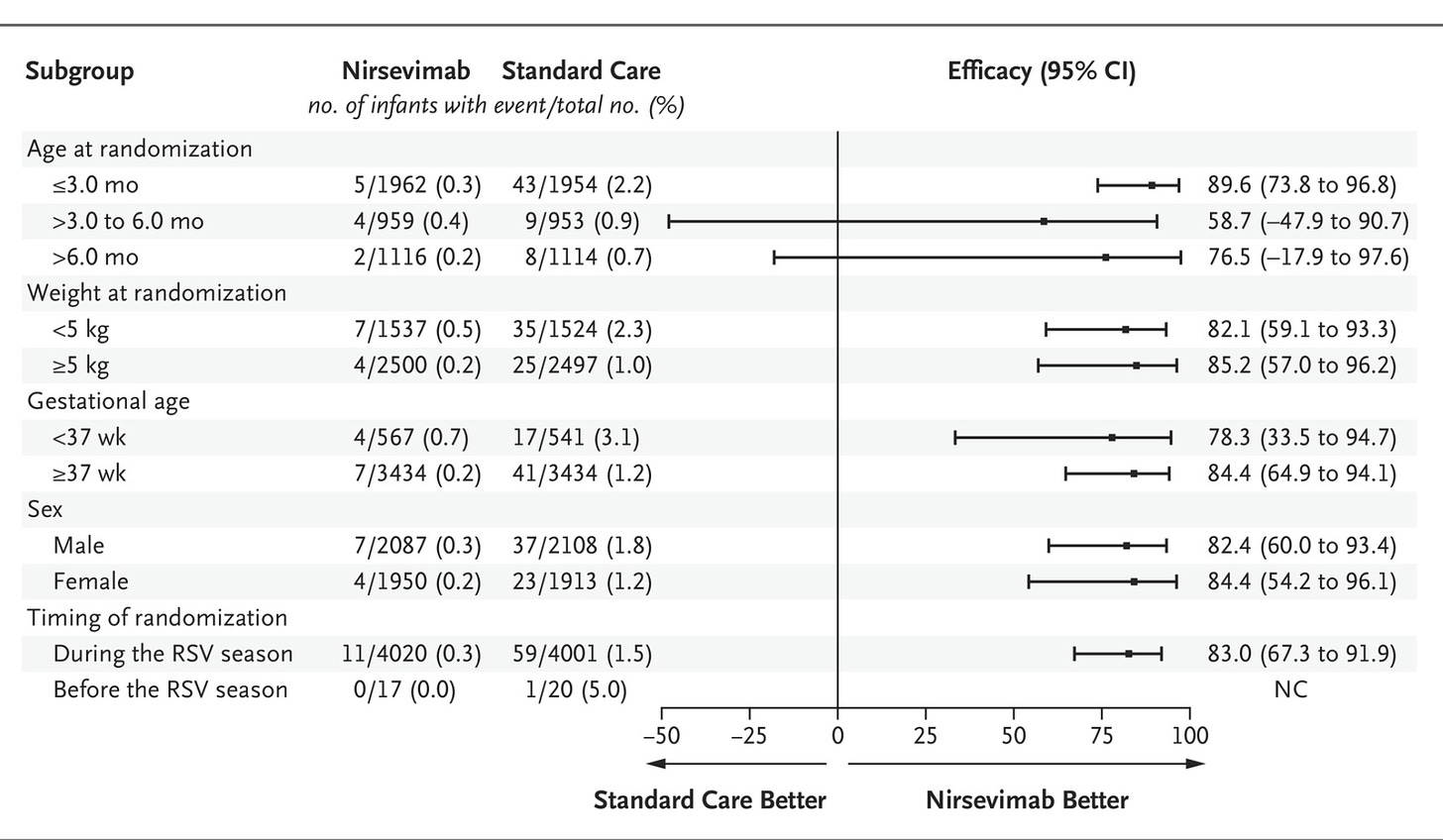

And here is the subgroup analysis of the primary end point:

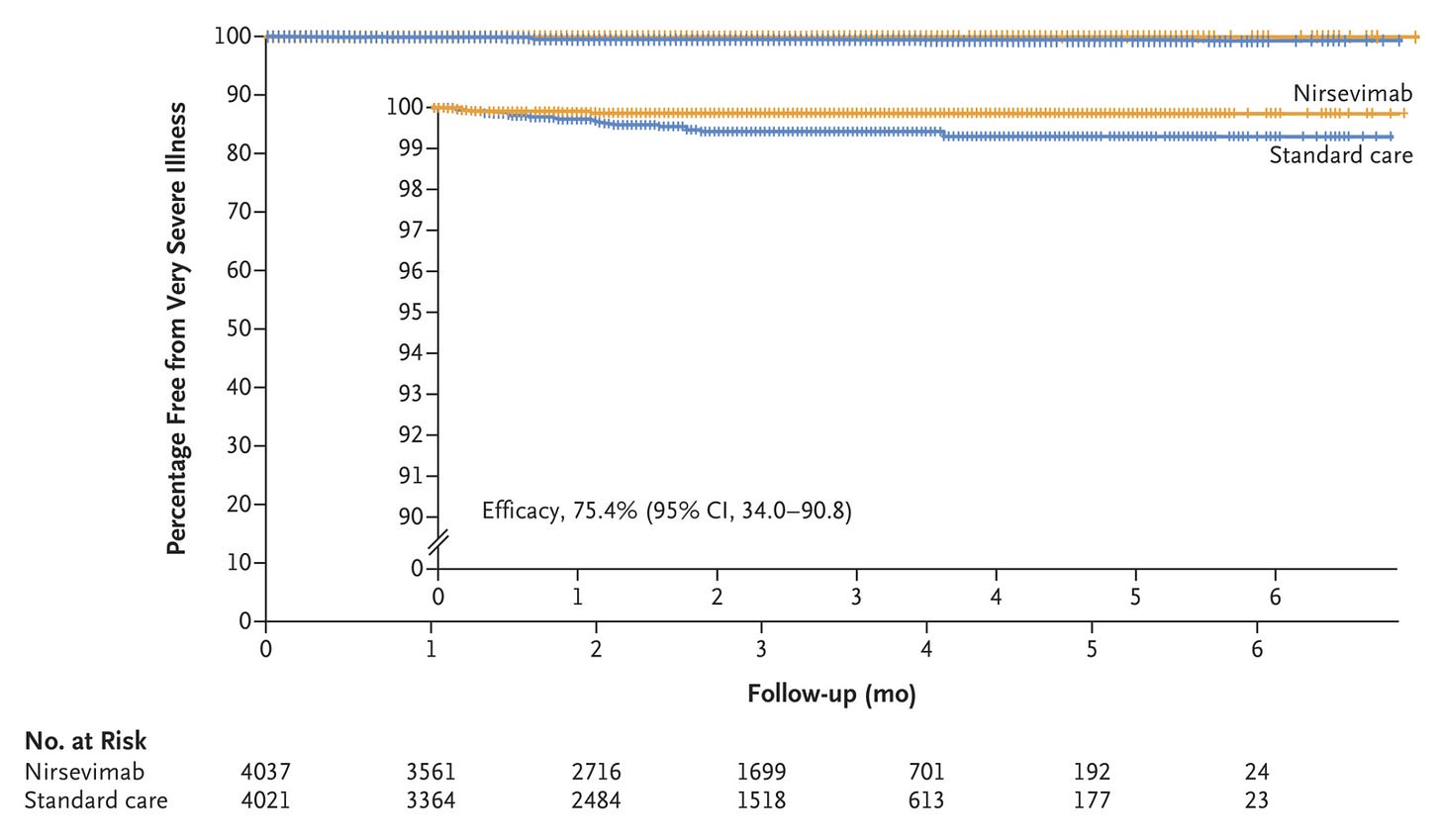

Here is the secondary end point of very severe RSV-associated LRTI (basically hospitalization + low O2 sat (<90%):

Safety Data

Interpretation

I’d like to break this down into a couple categories. Big picture, then thoughts on efficacy, and finally safety.

Big Picture: I briefly mentioned before that I am disappointed that we didn’t get a larger sample size out of this trial. The planned trial would have given us 14,000 infant nirsevimab recipients, which is much better than 4,000. That being said, this is still 4X the size of the recipients in MELODY (the phase 3 trial that led to approval), so it’s an improvement.

The open-label nature of the trial isn’t ideal, so all of the natural caveats apply. While we have to wait to get the finally one year follow up safety data, I would like to see two years, three years, etc. The reasoning being that you want to see whether there is any difference when these kids are inevitably repeatedly exposed to RSV in subsequent seasons. The authors readily acknowledge that this is a preliminary analysis with limited follow-up at this time.

I appreciate that they reported all cause LRTI hospitalizations, and we will address that data in the efficacy section. I would have liked all-cause hospitalizations as well, but this is better than MATISSE, which regular readers will be familiar with. The secondary end point of very severe RSV-associated LRTI is also quite helpful. This represents a hospitalization with low O2 saturation, which are the most meaningful hospitalizations.

Efficacy: We have seen the figures, but let’s look at the numbers:

“Hospitalization for RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection occurred in 11 infants (0.3%) in the nirsevimab group and in 60 (1.5%) who received standard care, which corresponded to an efficacy of 83.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.8 to 92.0; P<0.001) for nirsevimab during the 2022–2023 RSV season.”

“Very severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection occurred in 5 infants (0.1%) in the nirsevimab group and in 19 (0.5%) who received standard care, which corresponded to an efficacy of 75.7% (95% CI, 32.8 to 92.9; P=0.004) for nirsevimab during the RSV season.”

2 of the 5 in nirsevimab went to the ICU, 5 of 19 in standard care went to the ICU. One infant in the standard care group was intubated and received mechanical ventilation.

“Hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infection from any cause during the RSV season occurred in 45 infants (1.1%) in the nirsevimab group and in 98 (2.4%) in the standard-care group. These findings corresponded to a nirsevimab efficacy of 58.0% (nominal 95% CI, 39.7 to 71.2).

We can see that the absolute risk reduction (ARR) in all-cause LRTI hospitalization was 1.3%. The ARR for RSV-associated hospitalization was a similar 1.2%. The ARR for RSV hospitalization w/ low O2 sat was 0.4%. The subgroup analysis shows the the benefit was largely derived in the <3 month population of infants. This data seems to clearly show that nirsevimab is effective at reducing the risk of hospitalization due to LRTI in the first RSV season for infants that meet this inclusion/exclusion criteria.

One caveat that is important was brought up as a limitation in the discussion section, “Finally, infants without lower respiratory tract infection may have been hospitalized for reasons related to RSV infection, such as dehydration, and among 158 infants hospitalized for lower respiratory tract infection for any cause, 16 did not undergo RSV testing.”

The part about dehydration underscores the earlier point about my desire to see all-cause hospitalization. I hope to have access to those numbers when the final report comes out. The final data point begs the question of whether the 16 infants hospitalized with LRTI that did not undergo RSV testing were evenly distributed between the two arms of the trial. These 16 patients could meaningfully impact the calculated efficacy, in either direction, depending on which group they were assigned to.

Safety: This we will largely have to wait on, given the limited follow-up at this analysis, but we can look at what they do have. Table S2 and S3 of the supplement break down the numbers for adverse events, and only one category stuck out to me as potentially concerning. The big caveat is you have to be careful interpreting anything that happens in very small numbers, another downside of the reduced sample size in this trial.

That being said, the nervous system adverse events stands out as something to keep an eye on. Table S3 shows numerically higher serious treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE), with 11 vs. 2 nervous system disorder events seen in nirsevimab vs. standard care, respectively. I don't love that they broke down some of the systems-based adverse events in the safety table included in the main paper and left this out.

Final Thoughts:

HARMONIE seems to suggest nirsevimab is efficacious in the prevention of LRTI hospitalization in infants, particularly those <3 months of age within their first RSV season. I will emphasize some of the necessary caveats — this was open-label, we have not seen all-cause hospitalization, we have limited safety data and in my opinion a specific class of reactions to keep an eye on (nervous system adverse events), and we got less than a third of the participants we might otherwise have seen in order to assess safety data.

There is an entire additional discussion about the absolute benefit seen in this trial. If we were to focus on the very severe hospitalizations, the number needed to treat (NNT) would be over 200. I think it will help to have multiple seasons of follow-up data, but I am disappointed that we didn’t get the huge numbers we might otherwise have seen (~14,000 infant recipients).

Let me know if anyone has thoughts, critiques, etc.

Happy Monday

Dave-

Thanks for going over this. I'm a busy primary care pediatrician, and appreciate your analysis. I read this paper carefully yesterday. It's helpful to know I'm interpreting it correctly. I agree with you that it will be important to have long term data on impact after 2-3 seasons. I've heard pediatricians say that treated babies get RSV too, just don't get as sick, so they'll be the same as untreated babies the next season, but we don't know that to be true.

Based on this study, nirsevimab ONLY shows statistically significant efficacy in infants <3 mo, right?

I'm glad you focused on absolute risk reduction rather than relative risk reduction. I would have liked to see more information on the hospitalized children, and I'm guessing that's not provided because it doesn't help make the case for using this product universally. It was included in the previously published trial. In the context of our practice, it's very unusual for a child to be admitted for RSV LRTI unless they need supplemental O2 (very severe definition). In the previous trial, average length of stay was 2-4 days. I would guess the ones who were admitted for "not very severe" RSV had shorter stays overall, just admitted overnight for observation, or were admitted for something else. Wish I knew for sure.

NNT info is important to consider, I think the number is 288 to prevent very severe hospitalizations, right? Cost per dose is about $600 ($495 from vendor plus costs to administer). That would be $172800 to prevent one of those hospitalizations.

I'm particularly interested in this now because there have been shortages of the product, so it wasn't as widely used as expected. The shortages are now relieved, and CDC announced last Friday that pediatricians should be urgently getting this into all infants <8 mo. We're on the downslope of the RSV season for this winter, nationally and in my region (midwest). The efficacy of this product is obviously diminished when provided late in the RSV season since it won't last till next year, so we can assume that NNT and cost per episode prevented would be even more unfavorable.

I think this product will turn out to have some real value, especially for younger infants and those with vulnerabilities. But this is another example of regulatory agencies more interested in supporting sales of a product than thinking about it carefully. And that really bugs me. I hope a lot of people read your analysis. Thanks again!

Interesting post and I learned a lot from this comment as well!

In my mind, I think the cost of nirsevimab makes broad immunization seem economically untenable. With even a ARR of 1.3% for all-cause LRTI, there is very little is saved in spending for those specific hospitalizations. A cost effective analysis Shoukat et al. (with many assumptions taken for modeling) found that at about half the price it could be beneficial though.

Not sure how often (or if it’s fair for) the economics comes across clinicians minds but I have noticed very different treatment patterns for offering nirsevimab. I agree focusing on the most vulnerable children and newborns stand to gain the most from it.